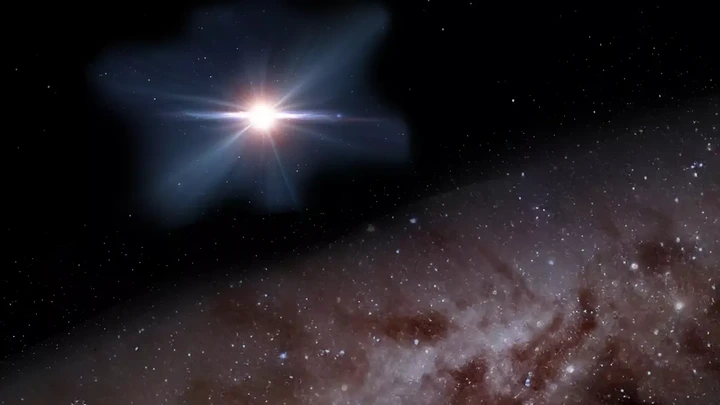

The recently identified "blazar," boasting a mass equivalent to 700 million suns, is the most ancient example of its type ever observed, altering our understanding of the early universe.

View pictures in App save up to 80% data.

Astronomers have identified a supermassive black hole that is emitting an enormous energy beam directed straight at Earth. This colossal entity, weighing approximately 700 million times that of our sun, is targeting us from a galaxy dating back to the early universe, around 800 million years post-Big Bang. This discovery marks it as the farthest "blazar" ever observed.

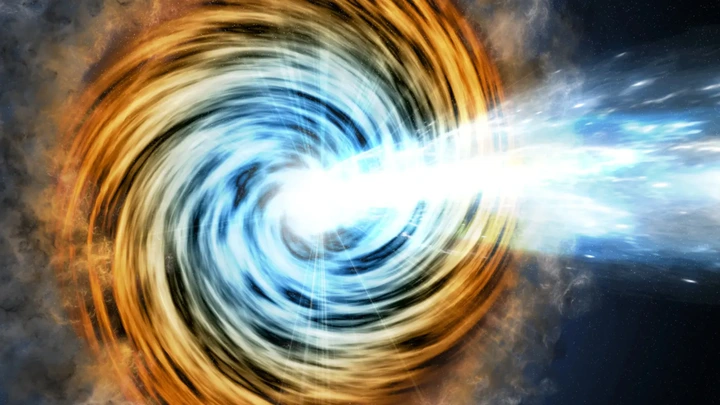

Some supermassive black holes, known as quasars, are so massive they can superheat the material doom-spiraling within their accretion disk to hundreds of thousands of degrees, at which point they emit huge amounts of electromagnetic radiation. The quasars' immense magnetic fields can sculpt this energy into twin jets that shoot out perpendicularly to accretion disks and extend well beyond their host galaxies.

By chance, some of these quasars point one of their twin jets directly at Earth, creating radio bright spots that pulse as these black holes consume matter. These black holes are known as blazars.

In the new study, published Dec. 18, 2024, in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers discovered a new blazar, dubbed J0410−0139, using data from multiple telescopes, including the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, the Magellan telescopes and the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope — all located in Chile — and NASA's Chandra observatory in Earth-orbit.

Radio emissions from this blazar have journeyed over 12.9 billion light-years to arrive at our observation point, setting a new benchmark for this category of cosmic entities. The astonishing age of this luminous giant may provide scientists with insights into the formation of the earliest supermassive black holes and the subsequent evolution of these galactic cores.

View pictures in App save up to 80% data.

"The alignment of J0410−0139's jet with our line of sight allows astronomers to peer directly into the heart of this cosmic powerhouse," study co-author Emmanuel Momjian, an astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Virginia, said in a statement. "This blazar offers a unique laboratory to study the interplay between jets, black holes, and their environments during one of the universe’s most transformative epochs."

The most ancient blazar discovered to date.

Fewer than 3,000 blazars have been discovered to date, and most have been located much closer to Earth than J0410−0139. The previous record holder for the most distant blazar was PSO J0309+27, which was discovered in 2020 and is around 12.8 billion light-years from Earth, making it around 100 million years younger than J0410−0139.

When viewed in the context of the universe's vast age, this age gap appears negligible. Nevertheless, during those 100 million years, a supermassive black hole could potentially expand by several magnitudes, rendering this a noteworthy advancement.

Finding one blazar at this distance hints that many other supermassive black holes existed at this point in cosmic history that either had no jets or beamed their radiation away from Earth, study lead author Eduardo Bañados, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, said in another statement.

"Picture this: you come across a story about an individual who has struck it rich with a $100 million lottery win," Bañados remarked. "Considering how infrequent such a victory is, it’s clear that numerous other participants in that lottery didn’t walk away with such a massive prize. In the same vein, discovering one [quasar] with a jet aimed straight at us suggests that during that era of cosmic evolution, there were likely many more [quasars] whose jets were oriented away from our line of sight."

The researchers will now hunt for more blazars from this time and are confident they will find some. "Where there is one, there's one hundred more [waiting to be found]," study co-author Silvia Belladitta, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, said in the statement.

Top-rated Choice

Top-rated Choice